Mr Opinion

Matt Yglesias and his discontents

In 2021, the pundit and blogger Matthew Yglesias decided to make some concrete predictions. He was responding, commendably, to the criticism that pundits rarely make claims for which they can be held accountable. They instead stick to arguments that won’t get them in trouble: normative rather than empirical claims; forecasts with no clear timeline; highly-charged but too-abstract pronouncements. And there’s our collective amnesia at work, too. When pundits do venture into the realm of concrete, time-bound, and falsifiable predicting, they can rely on us all forgetting the prediction by the time the answers roll in.

So, in the final days of 2020, Yglesias made a range of clearly-defined forecasts about the coming year and attributed to each a measure of his confidence out of 100.1 A score of 100 reflected absolute certainty; a score of 50 reflected total uncertainty. Anything below 50 implied he thought the event would be unlikely to happen. The predictions were mostly bread-and-butter fare for his publication, Slow Boring , which comments on policy and politics at a truly prolific rate. Joe Biden ends the year with his approval rating higher than his disapproval rating (70%), NO, went one example. The EU ends the year with more confirmed Covid-19 deaths than the US (60%), YES, went another.2

A year later, Yglesias dutifully shared his results. The scores were terrible. ‘This is a bad record’ wrote Yglesias. ‘So bad in fact that I want to curl up in a ball and give up rather than try again…I’m going to try to keep working at it, do another round, and improve my predicting skills.’

It was an admirable thing to admit. Here was a man who had built an entire career, and more than two media brands, on the claim that his was a voice worth listening to. By sheer force of reach, including more than half a million Twitter followers, Yglesias had held sway over Anglosphere public policy discourse for over a decade. At the time, it was reported, Slow Boring was read by swathes of the Biden administration.3 And here its founder and lead author was conceding that his ability to anticipate the future was at best limited.

It’s rare to see admissions like that among our pundit class. But Yglesias’ post wasn’t universally self-effacing, either. The lion’s share of the blame, he thought, should go to the difficult nature of forecasting, and to reflect this he gave his article the title “Predictions are hard”. Plus, he added, making concrete predictions was new to him. He figured predicting was much like running, a sport he had recently started getting into. ‘It turns out doing something new is really hard…I am hoping that if I keep working at it I will keep improving.’

But anticipating the future should not have been new to him—it is a constitutive component of public policy commentary. Because policy interventions are always future-oriented, prediction might even be foundational skill of the profession. The fact that forecasting is difficult—something no one will deny—is exactly why many people leave policy discussions to the best minds in town. Minds, supposedly, like that of Matt Yglesias.

There was something a bit dishonest in this professional pundit trying to let himself off the hook by claiming to be a novice at a core requirement of his own job. It doesn’t take much to see that a professional pundit’s relationship to prediction isn’t at all like his relationship to running, but a lot more like, say, a professional soccer player’s relationship to running. Being fast might not be sufficient for a football career, but it’s surely necessary… and there are no slow players in the Premier League.

Still, words like “good” and “bad”, “fast and slow” suggest some kind of benchmark. Yglesias was disappointed in himself, but his results might look more impressive when compared to other people. Prediction really is hard, after all. Perhaps other pundits would fare even worse. Could that be right? The only way to find out was to run a race next to him. So, the next year, my friends and I decided to join in. We took Yglesias’s 2022 predictions and each gave our own confidence in their likelihood. We then entered Yglesias’ forecasts into our little tournament, and we waited.

Perhaps it was a bit tough of us to compete against a guy without his knowledge, but there was no reason to think Yglesias hadn’t given these predictions his best shot. And Yglesias had been really explicit in his own post: the first time you make predictions is especially difficult, and you get better with practice. This would be his second time, and our first.

We started with a small handful of us—one group chat—and then, by invitation, brought in others we thought might enjoy playing. They were all smart friends of varying professions, though there were certainly no Superforecasters among us. We anonymised names to protect the identities of those in government or other sensitive roles, and we let the competition begin.

In the end 23 people participated. Those in my group chat all placed in the top 6. Yglesias finished back at 14.

I was recently reminded of all this when I opened my inbox to find a defensive Slow Boring article called ‘I’ve been right about some things’.4 Yglesias had been driven to reply to a piece from Luke Savage titled The Agony and the Ecstasy of Matt Yglesias, which picked up where Nathan J. Robinson had left off, in Dec 2024, in a piece called ‘Matt Yglesias Is Confidently Wrong About Everything’. That piece had followed a not-altogether positive 2023 profile of Yglesias in the Washington Post.

For Yglesias, Savage’s piece was one dig too many. ‘I sincerely cannot recall a single instance,’ Yglesias complained, ‘of a [leftist hater] brigader saying, “You know, I really hate Matt Yglesias, but it’s not literally true that he’s always confident or that he’s always wrong — for example, even though I disagree with him on every point of factional controversy between the left and the center-left, he also has a lot of banal progressive opinions like ‘abortion should be legal’ and ‘the government should give poor people more resources.’’’

If the “center-left” has any meaning, banal progressive opinions are surely necessary to its membership—to commend Yglesias for them would suggest he lives on the political right. Why, then, does he want to be applauded for being pro-choice? Why the desire for acknowledgement, the pained cry for a little credit?

For all his sins, Yglesias does in fact represent the apex of the political blogging form. He is a producer of a prodigious and unwavering tide of content that manages, in the main, to be sophisticated, sensible, and largely unremarkable, ingesting and metabolising policy information at a startling rate. His waking hours are dominated by the consumption and production of wonkish content. Few people could do what he does; even fewer would want to.

Far from confounding the issue, these accomplishments are the best starting place to understand the cyclical dynamic of bitterness between Yglesias and his detractors. His immense effort, instead of returning universal applause, attracts consistent and vocal negative attention. His labour has won him money and power, but not approval.

And that is why, rather than take criticism as information about himself, Yglesias can only externalise the blame. His critics are in fact pathological, exhibiting signs of what he calls “Yglesias derangement syndrome”. Like Donald Trump before him, Yglesias considers his opponents bizarre, resentful, and wholly unjustified. They are ‘haters’ who ‘know they can’t hurt me’ and instead ‘attempt to bully younger writers by making an example out of me.’ Their criticism of his views can only be understood as a failing of their own—never evidence of a failing of his own.

The adopting of Trump’s rhetoric of victimisation is one sign that Yglesias is not on firm ground. Parasocial relationships on the internet do, of course, create weirdness—hatred can, of course, impair judgement. But how much criticism someone like Yglesias should receive is a kind of unanswerable question—the answer is just going to depend on your own politics. And what can’t be questioned is that Yglesias is an active participant in, and knowing stimulant of, the dynamics he claims to abhor.

That participation happens first and foremost on Twitter, where Yglesias is always present, often pugilistic, and nearly always patronising. It is there, in front of 548.2k users, that Yglesias is most visible, and there that he is least restrained. Take this now-deleted exchange, where he first characterises students campaigning for Palestine as strategic, cynical wreckers before pivoting to a view that they are ‘idealistic young dupes’:5

This degree of viciousness is unusual for Yglesias, but the type of comment is characteristic. In fact comments of this sort have been so frequent and so consistent for more than decade now that, to many internet users, they are simply what he is known for.

And while Twitter is where his reputation was built, it’s not the only place where he actively courts discord. In longform, his method consciously and explicitly maximises opposition, a fact Yglesias concedes without self-reflection: ‘My view in general is that it’s good for the world to swing pretty aggressively at the discourse pitches that come down, because there are a lot of other people who are sort of “savvily” ducking controversies.’ That view is defensible enough, but only if we accept its costs. In practice it creates exactly the dissension—the “derangement”—Yglesias objects to.

And then there are the takes themselves. Immortalised in screenshotted headlines, they are the closest thing pundits have to concrete predictions, and the only mechanism by which pundits can be judged. That is why none of Zak, Savage, and Robinson can resist naming Yglesias takes that look ridiculous in retrospect. They are trying to hold the pundit to account.

I don’t envy them the task. After two decades of ‘swinging aggressively at discourse pitches’, Yglesias has left an extraordinary back-catalogue of takes to work through, such that the challenge for a Savage or a Robinson is less to uncover dirt on their opponent than to search among the dirt for the piece of muck that might best stand in for the rest. In his ferocious desire to swing at every pitch, he is the omnipresent batter-at-the-plate of the centrist Anglophone internet. He is Mr. Opinion.

This phenomenon has led to the emergence of a sort of canon of Yglesianisms. There is, of course, his original sin of supporting the Iraq war. There is the cheerleading of poor safety regulations after the 2013 Bangladesh factory collapse. There is his active cheerleading for Sam Bankman-Fried. Yglesias likes to argue that the routine invocation of these classic examples shows how rare they are, how high his ‘batting-average’ is. But as I have said, these core texts are there to stand in for the rest.

Worse, canons ossify. Anything that doesn’t make it in falls slowly from memory, such that what remains is taken to be all that there is. Reading through Zak, Savage, and Robinson’s complaints, as numerous as they were, I was struck instead by how few of my own personal grievances had made it on to their list. They had been swallowed in the tide. I had to review my own internet footprint just to recall them in any detail, but they are there. It was to a rank Yglesianism, for example, that I dedicated one the earliest articles here at Kitchen Counter:

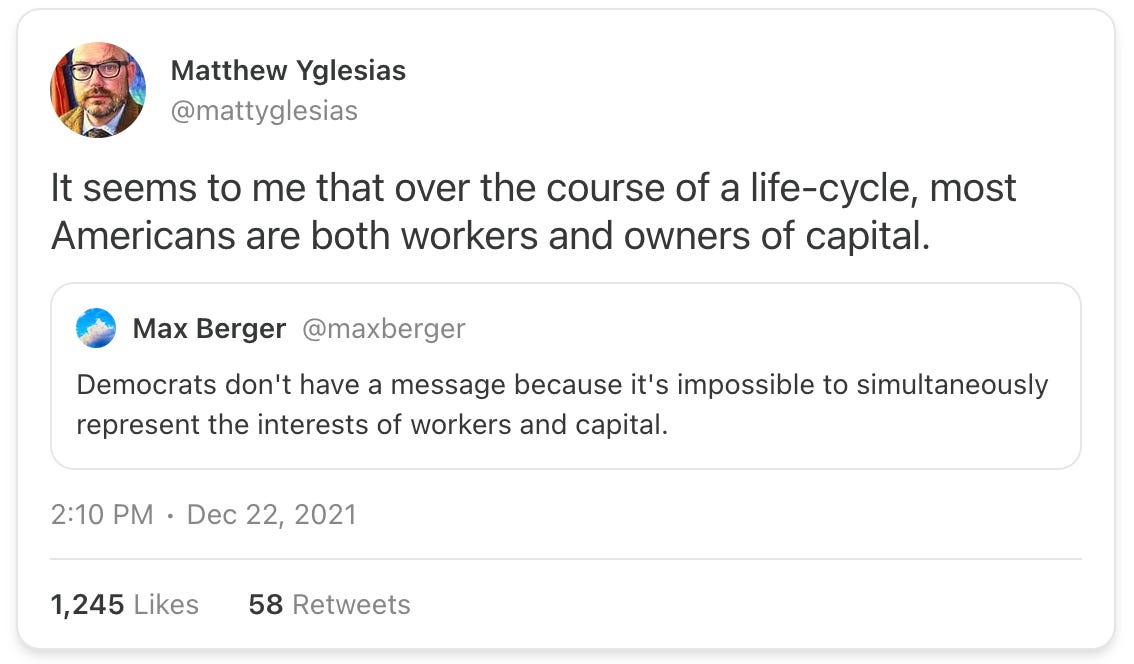

Already, all the way back in 2021, I thought that tweet was representative of the Matt Yglesias problem. It contained within it so much of what would cause pause in a more self-reflective thinker. There is the tone, which is sometimes called “smug” or “condescending” but which I think of, rather, as glib. There is the characteristically leftward direction of his attack, which has only increased in frequency and ferocity in intervening years as Yglesias has moved rightwards. And then there is the fact that he is wrong.

He was wrong not on some narrow, technical level (many Americans do own shares, of course, at some point). He was wrong instead only on the level his statement actually bears on his opponent’s argument. Capital ownership really is so unevenly distributed as to form distinct social classes—the existence of pension funds does not dissolve that fact. The data, which took me some hours to compile for that piece, are clear. But if I hadn’t compiled them, this Yglesianism, like so many others, would have been forgotten. He would not have been held to account.

This ultimately is the defining feature of so many Yglesianisms. They are outwardly antagonistic interventions that are noncontroversial in their narrow sense, allowing their author to retreat to safety when their bad faith gets the reaction it was designed to provoke. They are orthogonal to the point at hand. This bait-and-switch, bailey-and-motte approach to online discussion serves Yglesias’ ends well. The pedant scores a point, and the bigger progressive thrust is missed, even derailed. In the example above, I wrote thousands of words to correct his comment, but, by the time I published, the discourse had moved on.

What no one seems to want to say is that the real source of rancour between Yglesias and his discontents is their irreconcilable ends. Yglesias just wants different things from the world to his detractors. In fact, far from being identifiably “left”, Yglesias represents a liberalism that is simply conservative. If that adjective is controversial, it’s only because the term is no longer coherent in the US context, where “conservative” is used to refer to the Republican Party. But the Republicans are a reactionary rightist political party, not interested in conservation but in radical reshaping, and the role of conservativism, and defence of the status quo, falls squarely to the right wing of the Democrats. What they prioritise above all is order, stability, and growth.

This tendency has historically been identified with the centre-right, but around the world rightward ruptures have changed that, and nominally “left” parties have come to occupy the space of conservativism. In the UK, for example, Labour’s Keir Starmer is best thought of as a conservative. The US, meanwhile, has had to deal with the problem for much longer. There, the contrived and contingent constraints of the two party system have long cause conservative liberal politicians and pundits into unholy and ultimately bitter alliances with the left. It’s only in a particularly odd political world that it makes sense to pretend a person like Matt Yglesias is “centre-left”, and only in such a world that he would believe it about himself.6

That is why his relationship with the online left is so fractious—they’re just too-strange bedfellows, forced to share a party and, even more perversely, a political identity. Underneath it all, one group fundamentally disapproves of our economic regime. Yglesias does not.

This disjunct goes ignored in part because no one knows how to fix it, and in part because Yglesias likes to argue more about instrumental political strategy than he does about his substantive normative goals. In practice, these arguments about political means always paper over the fundamental question of political ends, and the fights about Democratic electability rarely articulate what world elected representatives are supposed to create. It’s no wonder, then, that Yglesian tactical recommendations for the Democratic Party, like “popularism”, tend in practice to advocate for the Party to become more right wing. Yglesias wants the Party to genuflect to voters on its right because he is a voter on its right. This is his prerogative, but the misnomer of “centre-left” is one we must leave behind. Irreconcilable differences are always felt more acutely when they emerge inside the family. We’d all be a lot happier, I think, if we stopped pretending they weren’t there.

Which means that we have, in the final analysis, an actively-antagonistic conservative commentator in control of an immensely profitable and influential blogging machine, unable to anticipate the future, uninterested in self-reflection, and loathful of being held to account. That makes him truly the perfect pundit—or, as Max Read wrote in his 2023 piece, ‘an exemplar of the form, for better and for worse.’ For Read, what makes Yglesias special is that he is uniquely unencumbered by shame. He has risen above it, zen like, and has built psychological mechanisms to ensure that being wrong never chastens him, never slows him down. He accepts no criticism and dismisses all detractors. People yell at him, he writes again the next day. Meanwhile his subscriber list grows. An exemplar of the form. All hail Mr Opinion.

He was following a longstanding practice in rationalist communities, best represented by orgs like Metaculus.

Yglesias’ method is a little muddled because he allows himself to make negative predictions with positive confidence levels.

Today the blog it has 20,000 paid subscribers, and is 15th on the Substack US Politics leaderboard.

I don’t pay for Slow Boring but I do have friends willing to forward me the odd email.

To see this more clearly, we can consider the wars between “wet” and “dry” conservatives in the UK and Australia in the final decades of the 20th century. It’s hard for me to distinguish Yglesias from a wet conservative.

Yglesias lives rent free in your head!

Have no clue who he is or why I should care he exists!

The problem around us is where is the real world? I suggest as a panacea watch Prime Minister, Jacinda Ardern's movie...If we need to be reminded of the greatness of human spirit...there lies a lot