Who is a capitalist?

Notes on a Twitter fight

When I was growing up, the people around me thought of society as made up of three types of people: rich people, poor people, and “the middle class”. This system was great for the purposes of identity (whether you were rich or poor, you thought of yourself as in the middle), but it didn’t tell you much. It suggested that society was homogenous, save for the degree of wealth inside of it. Some people were rich and some were poor, but the system had nothing to say about why that was.

It took me a while to adjust, then, when I got to uni and people were talking about a very different set of classes. Suddenly “middle class” – the identity to which I, and everyone I knew, belonged – wasn’t on the table. We were no longer supposed to identify with our relative level of wealth, but with the source of our income. Our choices were between “labour” (i.e. the working class) and “capital” (i.e. the owning class). You can trade your labour for money, or you can own the things that workers need to do their labour. The first group, we call workers. The second group, the people who own capital, we call capitalists.

Since the time Marx and Engels published Das Kapital, the left has put a lot of energy in trying to get people to see things their way. The reason is simple: for things to improve, they think, poor people need to get straight about what they have in common. They need to develop ‘class consciousness’. Once they do that, Marx thought, they’ll be able to see that the interests of workers will always be in tension with the interests of the capitalists. The two will always be arguing about how much each deserves to be paid for their contribution to production; one owning all the tools, the other doing all the work.

Getting people to see this is why Marx and Engels wrote The Communist Manifesto and why Jacobin magazine exists. The trouble is that the summary of Marxism in the Manifesto or in Jacobin or in the paragraph above is pretty vulgar. That’s the cost of popularisation. By the time you are dealing with big ideas in the public arena, they very often make pale imitations of their former selves. That’s particularly true for heterodox ideas trying desperately to popularise themselves. Models are simplified, ambiguities are ignored.

It’s against this backdrop that I’ve been thinking about this exchange online:

Max Berger reckons the Democrats are trying to appeal to the mutually exclusive interests of both workers and capital. As a rebuke to this idea, Matthew Yglesias ventures that most Americans access a little bit of both at some point in their lives. Seems innocuous, right?

Well, it caused a small furore on Twitter. One popular response quote-tweeted Yglesias with the words “what literally never opening a book does to a mf”. That set off a cascade of replies, tweets, and retweets, none of which felt particularly productive.

Before you go any deeper, let me give you the cheat code to understanding this and all Twitter fights: basically everyone is ungenerous. This is a stoush between warring factions of a small part of the American left wing media landscape motivated by a decade of petty grievances. I won’t go into too much detail, save to say that Yglesias, the heavyweight in this exchange, has a reputation, rightly or wrongly, for a kind of finger-wagging smug explainerism. That’s why no one trusted that he was operating in good faith, and why everyone ended up talking past each other.

That’s enough inside baseball. I’m interested in this exchange not because Yglesias’ gotcha undermines Berger’s point in the way he seems to think it does, but exactly because Yglesias seems to think it does. This is the centre-left media’s foremost policy wonk. He has a Substack read by half of the Biden Administration. But this exchange reveals that he either has not read modern leftist literature, or, if he has, he believes that Max Berger has not.

So let’s take a look. The backlash was sufficient that Yglesias was driven to follow up with: “My favorite genre of interaction on here is when thousands of idiots pile on to denounce an obviously true statement.”

It is obviously true that, thanks to the increased financialisation of the economy, some workers are able to own small fractions of capital. It wasn’t always the case. We didn’t have the instruments to make shares of capital available to all citizens. Instead, a small handful of capitalists controlled the means of production and never worked. Housing was yet to become an investment vehicle in the manner it is today, and invested superannuation didn’t exist.

Today, if you download Robinhood and buy $5 of TSLA, congratulations, you own capital. Things have changed. But this is so obviously true one might think it doesn’t need to be said. It’s a phenomenon commonly discussed in academic left wing literature, if not in the vulgar marxism of Twitter or Jacobin. But does it invalidate Berger’s point?

The first thing to say is that I’m pretty sure Yglesias is conflating capital with wealth, which isn’t quite accurate. But whatever, let’s run with wealth. The second thing to say is that wealth expectations over a lifecycle don’t undermine the tensions between labour and capitol today. The idea that a 25 year old might one day own their own home doesn’t dissolve the fact they are being exploited by their boss right now. But again, whatever.

None of that is really important next to this point: yes, the democratisation of financial products has given more people in rich countries exposure to capital. But there is clearly a difference between a person whose capital returns supplement their wage, and a person whose wage supplements their returns on capital. Let me cut out the economics lingo: if you need to exchange your labour for cash in order to put food on the table, your interests are not the same as people who don’t.

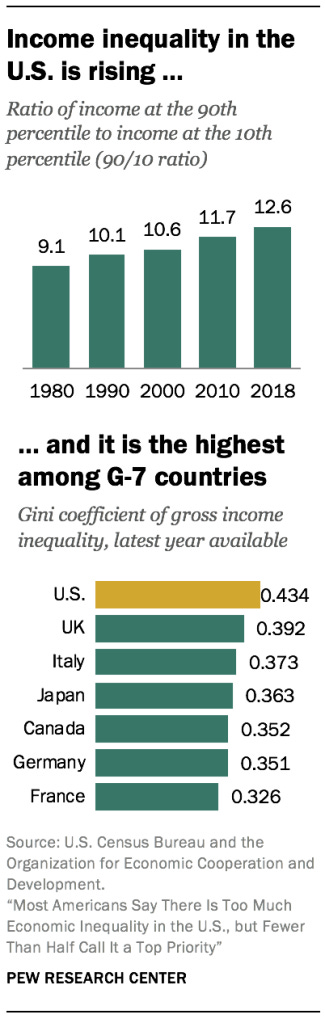

To get a clearer sense of this, let’s see how capital is distributed in our economy. To do this, consider the Gini coefficient for capital income inequality. The Gini is our measure of inequality on a spectrum of 0 to 1, where 1 is absolutely inequality. [Pew Research tells us that the gross income Gini coefficient (that’s income for both capital and labor) for the US in 2017 was 0.434, higher than any other G-7 country. But what about the Gini coefficient for capital income?

Is it perhaps 0.5? 0.6? No. Branko Milanovic, using data from the Luxembourg Income Study, puts the number at 0.9. “It is thus in all cases close to a theoretical maximum inequality of 1”, he writes. But that number may be under-doing it. “Since capital incomes among the top of the income distribution tend to be underestimated,” he warns, “true capital income Gini may be even higher.”

It’s a little hard to fully conceptualise how fucked this is. One way to do it is to imagine the most unequal country in the world, South Africa. The South Africans, off the backs of colonialism and apartheid, have managed to distribute gross incomes in their country to the tune of a Gini coefficient of about 0.63. That’s the most unequal country in the world. But the distribution of capital among rich capitalist nations is far, far, far more unequal than that. That is: the vast, vast majority of capital is held by a small minority of Americans.

But how much? Well, here’s Milanovic again: ‘Edward Wolff... showed that in 2013, the top 1 percent of wealth-holders owned one-half of all stocks and mutual funds.’ He goes on. “Perhaps even more revealing is that the top 10 percent of wealth-holders owned more than 90 percent of all financial assets.” Add to this the fact that, in 2014, the average wealth of the bottom half of Americans was $349. So while it’s true, as Yglesias says, that over their lifecycle most Americans will own some capital, it’s not much of a stretch to say, as Milanovic does, that “simplifying somewhat, we can say that almost all financial wealth in the United States is held by the wealthiest 10 percent.”

To my mind, the sheer density of capital ownership at the top puts a real puncture in Yglesias’s point. There really is a difference in the interests of the wealthiest 10 percent and that of everyone else. Relative to the top 10%, most people don’t own capital at all.

But what about relative to their own labour income? The strongest argument Yglesias could be making is that, even if they own little capital relative to rich people, most people in the bottom 90% will own enough relative to their wage to split their loyalties between the capitalist and working classes.

It’s clear that as you derive more and more relative income from capital, your economic interests correspondingly tip towards the success of capital. But do most people own enough capital over their lifetimes to be ambivalent about their economic interests? No. Unless your capital income begins to rival what you make from labour, your interests remain aligned with other people who rely on a wage to get by. But consider how much capital you need for your capital income to rival a typical wage. With average returns on capital over the last 100 years sitting at about 10%, you’d need about $400,000 to bring in $40,000. This, in a country where the median personal income sits at $35,805.

In a country that asks citizens to save for retirement by investing in the stock market via a 401(k), the success of that portfolio will naturally be of concern to everyday citizens. But unless they are approaching retirement, not one of these citizens would prefer to sacrifice their labour interests in return for more success in the capital markets. Why? Because their share of labour income is the only thing that allows them the chance to access capital in the first place.

What about well off people at the end of their lifecycle? This is the quintessential example for Yglesias’ point. People who have exited the labour market and instead live off the proceeds of their 401(k) have made a complete transition from the working class to the capital owning class. But this is simply to say that they are now capitalists. Their interests have rapidly shifted, and suddenly are opposed to the interests of workers. Their allegiances are in fact less conflicted than they were previously.

All this is to say that what Yglesias says is true, but does not bear much on Berger’s point. Given that the interests of capital and labour are analytically opposed, it doesn’t matter that some people own both. Favouring one over the other will naturally favour one part of a capital + wage portfolio while damaging the other. It’s true that at some point this is going to cause some ambivalence. To these people, as Yglesias suggests, it may even be attractive that the Democrats are clumsily trying to balance both goals. But as we’ve seen, many people will never have enough capital to have trouble choosing a side.

Of course, all of this is distinct from how people actually perceive their interests. There is not much class consciousness among the working class, and plenty of identification with the capital owning class – even among workers! Very many people overestimate their interests qua capitalists, and underestimate their interests qua workers. But that’s because the ideology of capitalism is so hegemonic that all of us are encouraged to identify with function of capital ownership, whether we ourselves own much capital or not. The increased access to financial capital among the working class only compounds this problem.

Coda

These points deserve their own post, but I thought it important to acknowledge them here:

One way to get clear about all this stuff is to think about CEO pay. CEO pay grabs a lot of headlines because the salary is always so much bigger than the employees. If you take nothing else from this newsletter, take this: please do not think about wealth this way. The problem with CEO pay has very little to do with their salaries and everything to do with other forms of compensation. That is, they receive capital.

Jeff Bezos is the perfect example. When he was CEO of Amazon, he took home about 80k per year. But because he owned a lot of Amazon, he was the richest man in the world. It is capital, not high salaries, that create billionaires.You guys (the people who receive this newsletter) are nearly universally members of what is sometimes called the Professional-Managerial Class. This is a term first coined by Barbara Ehrenreich used to refer to a stratum of people immediately underneath the pure capitalists in the class hierarchy.

These people mess up the old capital-labour Marxist binary because they draw wages that far exceed other workers. These massive wages are then transferred for capital. People in this class tend to be in the top 10%, but crucially, they continue to work. A marketing manager at Apple on 300k will pretty soon amass capital returning enough income to live. These people are not, to my mind, members of the working class.The effects of capitalist financialisation look pretty dire for leftists. If the interests of wealthier people are destined to align with capital as those people approach retirement, large numbers of people are going to vote on the side of capital even as the top 10% accumulate the vast majority of the earth’s wealth. Thankfully, market socialism has an answer. Capitalism’s tools must be used against it.

The way to create a fairer society while maintaining the advantages of capitalism is to just redistribute the capital. To do this, the government must fund a sovereign wealth fund using progressive wealth taxation. For this fund, every citizen is given one share and can watch as their own personal wealth grows alongside the wealth of their countrymen. Eventually the ownership of capital in the economy is redistributed among everyone. You don’t even have to get close to equal ownership for most social ills, like poverty, to disappear. The goal of socialism, in other words, is to make all of us capitalists.

That's really fascinating. So, too, the insights on on twitter social psychology. And thanks for butting up against the US border - in particular, the reason for the butting: your Colombia notes. Looking forward to reading that one.